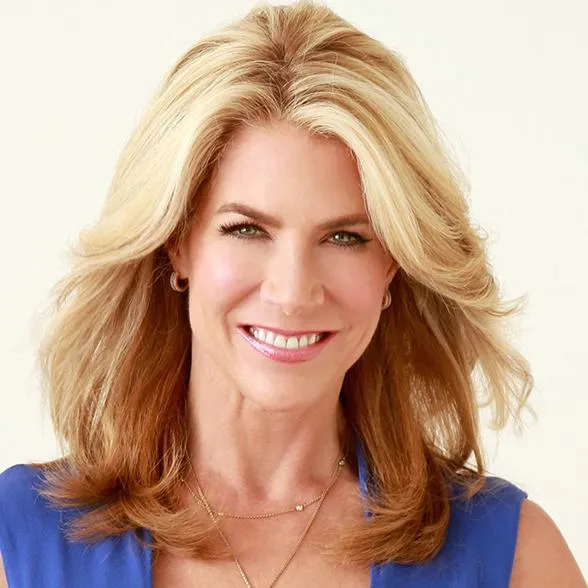

Dr. Joan Rosenberg

Comprehensive programs for corporations that support healthy behaviors for their employees both in and outside the workplace.

About Dr. Joan Rosenberg

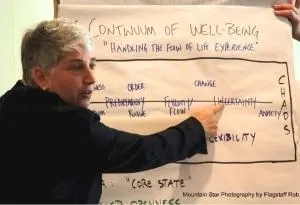

Dr. Joan Rosenberg provides tailored wellness solutions to the corporate sector, including seminars, interactive workshops, keynote speeches, and training tailored to meet your specific needs. These initiatives are designed to address the pressing mental health challenges faced by today’s workforce, positioning your company as a leader in holistic employee health.

Transform your life...at the speed of thought

Transforming corporations through specialized training and strategic guidance.

Corporate Consulting & Training

If you're planning a significant corporate event or an engaging lunch and learn session, consider Dr. Joan Rosenberg as your expert speaker. Renowned for her expertise in emotional mastery and personal growth, Dr. Joan will not only uplift but also deeply inspire your team. Her specialized training sessions are tailored to invigorate and empower, making them a perfect fit for organizations looking to enhance team dynamics and individual well-being

Keynote Speaking

Elevate your next conference or corporate gathering with a keynote speech from Dr. Joan Rosenberg. Renowned for her expertise in emotional mastery and transformative personal development, Dr. Joan delivers powerful, engaging presentations that inspire audiences to new heights. Her keynote addresses are perfectly tailored to motivate change and growth, ideal for any event seeking to leave a lasting impact on its participants.

Online Coaching Programs

Enhance your personal and professional growth from anywhere in the world with Dr. Joan Rosenberg’s Online Coaching Mastery Programs. These comprehensive online programs are designed to provide deep insights into emotional mastery and effective personal development. Dr. Joan's expert guidance will help you navigate challenges and unlock your full potential these programs offer the tools and support needed to achieve lasting success and fulfillment.

Jack Canfield

NY Times Best Selling Co-author of the Chicken Soup for the Soul series and The Success Principles

Joan’s approach is simple, practical, and effective. It represents a significant breakthrough on the path to success. If you want unwavering confidence to pursue your goals and dreams, then this will guide you to it.

JJ Virgin

New York Times bestselling author of The Virgin Diet and JJ Virgin's Sugar Impact Diet

As for so many others, Dr. Joan Rosenberg has been my lifeline…There is a special kind of hope that comes from finally understanding that fear is not your enemy. Until you experience it yourself, it’s hard to imagine what a difference 90 seconds can make.

Ron Howard

Film director, producer, and actor

Every once in a while, you meet someone capable of turning conventional wisdom on its head. Dr. Joan Rosenberg is both a brilliant clinician and compassionate presence. Her book inspires and invites people to be authentic, to become their best and most fully expressed selves. It’s a game changer for anyone ready to take their life, relationship, and career to the next level.